Turtle Blog

2017 SEE Turtles Annual Report

2017 was a great year for both sea turtles and SEE Turtles. Research is showing an improving situation for a number of sea turtle populations around the world and several important nesting beaches had their strongest year on record. SEE Turtles became an independent non-profit, reached the 1 million hatchlings saved milestone, our conservation trips had their biggest impact to date, and our Too Rare To Wear program got off to a great start. And the best is yet to come!

Our decision to become an independent non-profit was a tough one. We had great support from our past fiscal sponsors Oceanic Society and The Ocean Foundation that helped us grow and thrive. Being an independent organization though will allow SEE Turtles to both grow and become more efficient. Our overhead costs will drop, allowing us to invest in growing our programs and saving more turtles over the long-term. We are very thankful to our wonderful new board of directors for and to Oceanic Society and The Ocean Foundation for their help in this transition.

Looking back, 2017 was the year we hit our first major milestone for our Billion Baby Turtles program, one million hatchlings saved. We also raised more than $6,000 to help restore Puerto Rico sea turtle conservation efforts. We’re thrilled to be able to support many important sea turtle nesting conservation programs and look forward to increasing our support for these programs and bringing in new partners.

Our Too Rare To Wear campaign, which started in late 2016, made great progress in elevating the issue of the turtleshell trade in the tourism industry, with more than 80 tour companies and conservation organizations partnering on the campaign, innovate educational tools, a ground-breaking report, and millions of people reached. Our Sea Turtle Conservation Tours had more than 100 travelers participate in trips with roughly 400 volunteer work shifts and more than $100,000 generated for turtle conservation and local communities.

Looking ahead, 2018 promises to be another exciting year. 2018 is our 10th anniversary and hopefully passing $1 million generated for conservation and communities. We are planning a month-long celebration with discounts on tours, giveaways, and much more, be sure to follow us on social media to learn more. We will also be expanding Too Rare To Wear to Asia, offering a great slate of conservation trips, and expanding our support to new nesting beaches through Billion Baby Turtles.

Thank you for joining us for this ride. SEE Turtles would not exist without our wonderful donors, travelers, schools, and partners.

-Brad Nahill, President

One Million+ Hatchlings Saved!

We're reached our first major milestone in our Billion Baby Turtles program! Since our official launch in 2013, we have provided enough funds for our network of turtle conservation partners around Latin America and the Caribbean to save more than 1 million hatchlings (1,230,460 to be exact)!

To celebrate, we are taking this opportunity to raise funds for sea turtle conservation work in Puerto Rico, which was recently devastated by hurricanes. Every donation will be matched and our goal is to raise at least $5,000 to help the Vida Marina project of the University of Puerto Rico rebuild their programs after the storms. We are also holding a month of promotions to celebrate, giving away a gift pack of fun turtle stuff on each of our social media platforms.

A huge thanks to every donor, sponsor, and traveler for helping us reach this goal and our deep appreciation goes to all of our partners who spend countless hours walking dark nesting beaches to save these extraordinary animals. It is our pleasure to be able to support your work!

Billion Baby Turtles Surpasses 1 Million Sea Turtle Hatchlings Saved

Beaverton, OR, Nov. 1, 2017 - Billion Baby Turtles has helped conservation organizations across Latin America save more than 1 million sea turtle hatchlings. Recent research has shown that when sea turtle nesting beaches are protected, endangered populations can recover. Billion Baby Turtles, an initiative of the conservation organization SEE Turtles, brings together sponsors, patrons, schools, and travelers to raise funds that go to helping grassroots organizations that work on important turtle nesting beaches to protect turtles, their eggs, and their hatchlings from poaching.

Since 2013 the initiative has helped save approximately 1.2 million hatchlings by giving more than $200,000 in grants to 17 organizations in 9 Latin American countries. For every dollar donated, 5 hatchlings have been saved and roughly 90 cents of every dollar have gone to conservation efforts. Grants have supported programs restoring five of the seven species of sea turtles found around the world.

“The goal to save a billion baby sea turtles is wildly ambitious, and through the dedicated leadership of SEE Turtles we now know it’s totally within reach,” said David Godfrey, executive director of the Sea Turtle Conservancy. “It’s very exciting to see the campaign surpass a million saved hatchlings. STC is proud to be helping SEE Turtles reach its lofty goal through a nest protection program we’re carrying out in Panama with funding from the Billion Baby Turtles initiative.”

Protecting nests and hatchlings not only helps to bring endangered sea turtle species back from the brink of extinction, it also helps other species by increasing sources of food for birds, fish, crabs, and other animals. In addition, turtle watching has become an important source of income for many coastal communities and observing and participating in saving sea turtles and hatchlings has been shown to have emotional benefits for travelers and local residents alike at turtle nesting beaches.

Billion Baby Turtles has provided nearly 50 grants to date, ranging from $1,000 to $10,000. The initiative prioritizes small, community-based organizations working to protect beaches that have few other sources of funding and focuses on the most endangered populations of sea turtles. The largest numbers of hatchlings protected have been at Colola Beach, Mexico, where researchers from the University of Michoacan have worked for decades to bring the East Pacific green turtle back from near extinction. Our support has helped to save more than 600,000 hatchlings at this beach. Last year the East Pacific green turtle was downlisted, a sign of a positive trend towards recovery.

Funds are raised from a variety of sources including business sponsors, SEE Turtles conservation tours, individual donors, schools, foundations, and sales from the SEE Turtles online store. Sponsors and foundations have provided roughly half of the more than $200,000 raised, while tour income and individual donations have provided 15-20% each. 2017 was the best year yet for the initiative, with more than 400,000 hatchlings protected, an increase of nearly 25 percent from 2016.

Exploring Belize’s Wild Side by Boat, Snorkel, Canoe, & Inner Tube

Manatee!

No sooner had our boat pulled up to the coral reef for our planned marine life survey, than someone had spotted the long rounded shape of the marine mammal passing by our anchored boat. This being my first opportunity to swim with these extraordinary creatures, I quickly slipped into the water while our group was getting geared up with snorkels and fins.

Manatees are often wary, so I tried to not to scare this one off before everyone was able to see it. But after a few minutes, it was clear that this one not only didn’t mind our presence, it seemed quite curious about us. Several times the female manatee (who we nicknamed “Manuela”) would swim directly toward people in our group, passing just a few feet below them before surfacing for air. Manuela stayed with us for around 45 minutes, eventually deciding she had enough and swimming on.

This manatee encounter was just one of the first activities of our weeklong adventure to Belize with Nature’s Path, the largest independent organic breakfast company in the world. SEE Turtles has partnered with their EnviroKidz line of kids cereals since 2008, and this was our second trip with them to explore wildlife conservation programs with winners of their “EnviroTrip” sweepstakes. We had along with us families from the US and Canada who won out of more than 7,000 entries to the contest.

EnviroTrip Winners from the US & Canada

Our group first met up at Sea Sports, a dive shop in Belize City run by Linda and John Searle, who also run EcoMar, a research and conservation organization focused on marine wildlife. After a short boat ride to their research station on St. George’s Caye, our group met up for an orientation and delicious dinner and to sleep after the long flights from North America.

Our first activity was dolphin watching and we were lucky to be joined by marine mammal research Eric Ramos, who has spent years observing bottlenose dolphins and manatees living in the Belize Barrier Reef. The sea was calm as we headed south towards Gallows Point to look for bottlenose dolphins, though we didn’t spot any for a while. Eventually we saw a single dolphin nearby and stopped to watch him as he swam around our boat. Eric put his drone up into the sky to keep track of him and record video while we watched from the boat. On our way back to St. George’s, we came across a group of 4 more dolphins, including one calf, and watched as they fed.

Our special manatee moment came that afternoon, derailing our plans to snorkel the reef until another day. While we hung out with Manuela, a fisherman working with EcoMar caught a loggerhead turtle that was feeding on discarded catch from a fishing boat, so that we could attach a satellite transmitter on her shell to follow where she goes and learn more about the life cycle of these turtles.

Manuel from Nature's Path watching over Hope as her transmitter is attached

We brought the female loggerhead, who we named “Hope” after some our participants, back to the research station. The process of attaching a satellite tag is quite time consuming, with multiple applications of epoxy, each taking an hour or more to dry. The shell was cleaned, barnacles were removed (to allow space for the transmitter), and then the shell sanded to make it level. While that was done, we measured and weighed Hope, who weighed it at about 130 lbs. That evening, we put Hope in the water and waited eagerly for her tracker to start sending signals. That was just day one!

For day two, we headed back to Gallows Point to snorkel the coral reef, where we saw many fish, species of coral, sea fans, sponges, and other ocean life. The afternoon was dedicated to the queen conch, the beautiful mollusks that are one of the country’s biggest fish exports (after lobster). With so many of the conchs being taken by fishermen, Ecomar has been running surveys to determine their key spawning grounds. Our group split into two and did three transects, where we put down a line and looked for conchs on each side. When we found them, we measured them to determine their age and then returned them to the water. In less than an hour, we found roughly 100 conchs, almost all of them juveniles.

The morning of day three was dedicated to giving back to this special place. First up was a beach clean-up, where we filled 10 large trash bags in a short time. Even small islands like this one are not immune to the tons of plastic that end up in the ocean every year, threatening sea turtles and other ocean life. After that, we helped to install speed limit signs around the shallow areas behind the island, which were made with funds from EnviroKidz. This area is an important feeding area for the West Indian manatee and they are very susceptible to boat strikes, which is one of their biggest threats. Boats regularly speed quickly through this area, so by establishing an area where boats need to go slowly, these manatees will be less likely to be struck.

Linda & John Searle of EcoMar with the new speed limit signs that will reduce manatee injuries

In the afternoon, we headed out for another snorkel and we were again in luck. We anchored near another fishing boat, which had two loggerheads, two spotted eagle rays, and a whole bunch of stingrays hanging out to get a free lunch. We watched as they hovered around the seagrass floor looking for scraps of lobster, lionfish, and other discarded catch. Then heading off to the nearby reef, we came upon two more manatees, who were less curious than us about Manuela.

Day four, we packed up our things and headed back to Belize City to meet our transport to Crystal Paradise, two hours inland. We settled in to the rooms and then headed out for a fun canoe ride floating down the Macal River as cormorants flew overhead and iguanas sunned on trees.

To complete our exploration of the waters of Belize, our final adventure was cave tubing on the Caves Branch River (with some ziplines thrown in for the kids.) Our guide Erick connected our (lucky) 13 inner tubes together and we slowly floated into the first cave, which we had all to ourselves. He explained how the Mayans had used these caves for thousands of years as part of their ceremonies and pointed out interesting and beautiful stalagtites and stalagmites along the way. Our last day wrapped up with a fun dinner, thanking the great folks at Nature’s Path for helping these families to experience such a special week of wildlife and adventures.

Learn More:

Wild(life) Party in Baja

Arriving to the Los Cabos airport in March almost feels like waiting in line at a summer pop music festival. Hordes of college students with Greek letters fill the security lines; the anticipation of the upcoming parties is palpable. Fortunately our group left that scene behind the moment we hopped into our shuttles, the only wild time we were looking for was with the incredible ocean wildlife that lives in the Gulf of California and Magdalena Bay.

Our first wild encounter was the whale sharks that feed in the waters off La Paz. Ocean currents trap boatloads of plankton in the bay, creating a perfect spot for mostly juvenile (but still giant) whale sharks to feed. We met with Manuel Rodriguez from the Whale Shark Research Project who is studying these magnificent animals in the hopes of creating a protected area here to prevent these sharks from being struck by fast-moving boats leaving and entering the marina in La Paz.

It didn’t take long to spot the first dorsal fin breaking the calm waters. Our boat set up ahead of the path (out of the way though) of the whale shark and a couple of our participants hopped in to watch it swim by (and kick hard to keep up). Over the next couple of hours, our group, split between two boats, had several opportunities to snorkel with these amazing animals, which ranged from roughly 10 feet long to a bigger one possibly as long as 30 or more feet.

Overhead view of Balandra Beach

Our next stop was Balandra Beach, voted one of the country’s most beautiful beaches. But first was a detour to visit a colony of sea lions on a small island, followed by a group of bottlenose dolphins that joined us for a spell, at times traveling with us at the front of our boats. We then headed into Balandra Bay, an incredible range of blues set against the stark brown land. Balandra is a popular hangout spot for La Paz residents, who resisted efforts to put a large resort on the bay and helped to protect this area for everyone who wants to visit.

Our plan to return to the Gulf and visit the island of Espiritu Santo the next day was foiled by high winds, so instead we visited the beautiful town of Todos Santos. After a stroll around the town visiting the many artisan shops, we visited the hatchery of Todos Tortugueros, a local sea turtle conservation organization that protects the nests of olive ridley, black turtles, and the occasional leatherback turtle that nests near the town.

After two nights in La Paz, we then packed up and headed across the peninsula to Magdalena and Almejas Bays. On the way to our tent camp, on a strip of dunes between the two bays, we headed out to look for the gray whales that calve here. It didn’t take long to find the whales, and while none of them decided to say hello (these whales are the only ones in the world to sometimes approach boats), we had a chance to observe mothers and calves spyhopping, breaching, and feeding.

As we approached our camp, we spotted a seemingly out of place wild animal, a bald eagle standing on a sand bar. While this bird is now a fairly common site in Portland, Oregon, where many of our group came from, it was strange to see one in such a completely different landscape, though we learned that this area is the southernmost part of their range.

Upon arrival at our camp, we were introduced to the RED Travel Mexico staff who did a fantastic job at making us welcome. The tents were spacious with cots and blankets for the cool desert evenings. The food was prepared with love by the excellent chef Hubert, formerly a turtle poacher who now dedicates his time to supporting ecotourism and turtle research for Red. Our guide Alonso, a goofy and friendly marine biologist, helped to keep the group entertained with his great stories and deep knowledge.

The next morning, Jesus “Chuy” Lucero of the Grupo Tortuguero, led our group to a spot in the bay to set nets to catch black sea turtles (a sub-species of green turtles) to study and release. It didn’t take long to catch the first turtle, which Chuy pulled into his boat within a few minutes of our arrival. By the time that one was done, we had another turtle already caught and we headed to the beach to collect the data. Our group took turns with various tasks including helping to measure the turtles, weigh them, tag them, collecting the information on data sheets, and lastly releasing them into the ocean. In all, we studied and released five turtles, most of which were juveniles who prefer this bay due to its rich seagrasses. In addition, another nine turtles were caught for other guests at the camp to study, for a total of fourteen turtles studied in our three days at the camp.

Chuy (left) and Hubert (right) studying a black turtle

Once the turtle research was done, we had another opportunity to go whale watching. While the majority of whales had already headed back north up the Pacific coast on their way to Alaska to feed, many mothers and calves were still around and we had many opportunities to take photos and watch their fascinating behavior. Each day after our activities, we took a short walk across the dunes to the Magdalena Bay side to watch the beautiful sunsets and then back to camp for a delicious dinner and sit by a warm fire.

On our final morning, we took a short boat ride to a huge set of dunes, climbing up to the top for an incredible view of both bays and the surrounding islands and mainland. As if we hadn’t seen enough ocean wildlife over the week, a pair of dolphins were visible feeding from the top of the tallest dune. We then headed back to La Paz for a final celebratory dinner before our return to Los Cabos the next day for our flights home. During the week, we helped to support research into whale sharks and sea turtles and proceeds from the trip helped to fun Red’s community development work as well as protecting more than 1,300 hatchlings through our Billion Baby Turtles program.

Hawksbills Turtles Are Too Rare To Wear

One curse in working in wildlife conservation is that many of us after a while develop habits of searching out the threats to the animals we work to save all around us. With sea turtles, that includes finding plastic bags on the beach or watching people touch turtles while snorkeling. One habit I picked up years ago while working with leatherback turtles in Costa Rica was to look out for turtleshell jewelry whenever walking around the tourist town of Puerto Viejo.

So last summer when I found myself souvenir shopping with my daughter in the beach town of San Juan del Sur in Nicaragua, I ended up spending more time mentally cataloging the abundant turtleshell products for sale by the vendors and in the stores than actually looking for things to buy. I told my daughter that we wouldn’t be buying from anyone who sold those products and against my better judgment ended up arguing with a couple of the vendors about the legality of their actions (it is illegal to sell in Nicaragua but rarely enforced). After more than an hour, so many places sold turtleshell that my daughter begged me to just let her buy a braided bracelet anyway so we could stop shopping and go to the beach.

Turtleshell for sale in Nicaragua. Photo: Paula von Weller

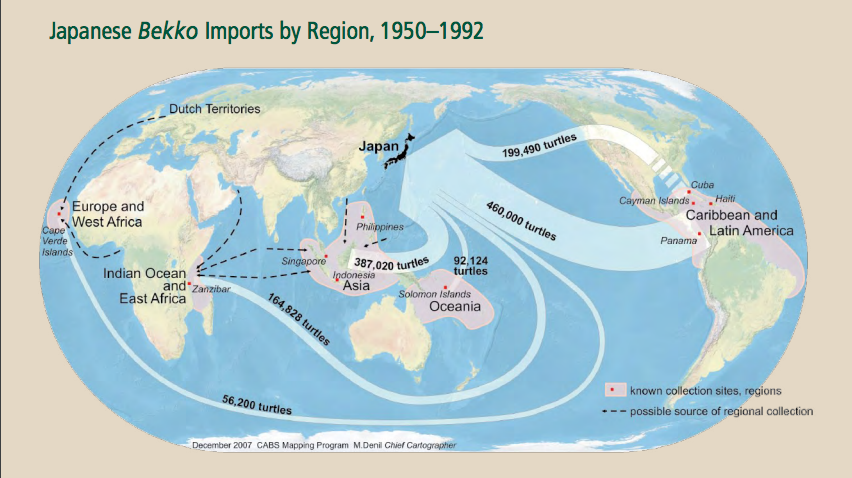

Turtleshell (sometimes incorrectly called “tortoiseshell”) comes from the critically endangered hawksbill sea turtle. The beautiful color pattern of gold, amber, and brown (which helps them hide in coral reefs) combined with the ease of shaping the carapace (made of keratin) make this material popular for artisans, kind of like a natural plastic. The trade in the shells goes back thousands of years and was a multinational business for many years. Most of the shells were exported to Japan from around the world, where an entire industry of artisans made exquisite products out of the “bekko” as it’s called there, similar to the ivory carvers of China. Over a 50 year period, an estimated 2 million shells were shipped to Japan, which devastated hawksbill turtle populations around the world according to an excellent article in State of the World's Turtles (see graphic below).

Graphic from State Of The World's Turtles, Volume 3

Having worked with sea turtles my entire career, I knew this continued to be a problem but had no idea on how large of a scale the sale of turtleshell products currently is. Though the legal end of the international trade of their shells was finally outlawed as part of the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) in 1992, hawksbills have yet to recover their numbers. Estimates of the total number of adult female hawksbills worldwide range from only 15,000 – 20,000 (since the males don’t come ashore to nest, they are impossible to count) and they continue to be listed as critically endangered by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Hawksbills are not just a pretty shell; they are critical to the health of coral reefs, sometimes referred to as the “engineers of the coral reef.” These turtles primarily eat sea sponges, which compete with corals for space. Without hawksbills around, the sponges can take over and crowd out the coral. Sea sponges can be toxic to some animals; hawksbills are one of their few predators and can eat an estimated 1,000 of them in a year.

These reptiles are also important for coastal economies and divers and snorkelers. Many people flock to tropical reefs around the world hoping to spot them gracefully swimming in search of food, bringing in billions of travel dollars and providing lifelong memories. Unfortunately it is also many of those travelers who, sometimes unknowingly, take a piece of these turtles home with them as souvenirs.

The good news is that travelers can be part of the solution and help end the demand for turtleshell products. Too Rare To Wear is a new campaign that SEE Turtles is helping to launch that is educating travelers about turtleshell and how to avoid it. We are encouraging people when souvenir shopping to not only but something different, but to avoid shopping anywhere that does sell it, and most importantly, letting the people selling these products why you won’t buy anything of theirs.

Learn more about this issue, read the guide to identifying turtleshell, and take the pledge to avoid it at TooRareToWear.org.

Cover photo by Julie Suess.

Worth The Wait: Sea Turtles and Cuban Art In Many Forms

Arriving to Jose Marti Airport in Havana, the first hint you are somewhere different is the wait to get your bags. The throng of people standing around the two baggage areas, barely able to stand in the three hour wait to get bags checked for a 30 minute flight. The pavlovian response you feel whenever a new bag drops onto the conveyor, only to realize it’s not your bag.

The good news is that Cuba is totally worth the wait.

Once our group, participants in our Cuba Sea Turtle Volunteer Expedition, all got through customs and onto our bus, the real adventure began. Our intrepid group of travelers from across the US remained enthusiastic despite the arduous journey from Miami. One by one, we dropped the group off at their homestays, Cuba’s version of AirBnB, for some downtime before dinner. That dinner was the highlight of the first day, a fabulous multi-course meal at San Cristobal, a well-known paladar (Cuba’s unique family-owned restaurants set in former homes) where President Obama dined on his recent visit. The ornate décor combined with the creative menu, mojitos, rum, and cigars was the perfect introduction to this country.

After dinner, those not drained by the long day headed out to the Fabrica de Arte (the Art Factory), a unique Cuban institution. Few cultures in the America’s are as supportive of the arts and this museum/night club is the perfect example. A former cooking oil factory given to a group of artists, the Fabrica is an extraordinary mix of art forms, from photography and painting exhibits, to live music, a DJ, and a movie theatre (currently playing: Hail, Caesar!). The line outside was around the corner all night, something rarely seen at an art museum in the US.

But good food and the arts were not our primary reason for the visit. Our group was the first international group of sea turtle volunteers to come to Cuba, part of a partnership between SEE Turtles, Cuba Marine Research and Conservation, and INSTEC, a Cuban government agency in charge of the turtle conservation program at Guanahacabibes National Park where our group was headed the next day. Guanahacabibes is one of the country’s most important turtle nesting beaches for green and loggerhead sea turtles.

We met our bus early the next morning for the long drive to Guanahacabibes after a quick stop to pick up Dr. Julia Azanza, the biologist in charge of the conservation program (and her adorable son Dario). Our group stayed at the Maria La Gorda resort, named for a woman who by some accounts was the adopted mother of a group of pirates that once lived on this remote stretch of coast on the far western point of the island. After dinner the first evening, Dr. Azanza gave a presentation on the research program, which she has directed for more than a decade.

The next day our group headed out with Osmany, a ranger for the park to look for some of the unique avian critters that live here. Osmany is so good at bird calls that it was often difficult to tell where a call was coming from, him or the birds. In a short span of time, we got to see several bee hummingbirds (the world’s smallest bird at just 2 inches tall), the Cuban trogon, the emerald hummingbird, and many other species.

Bee hummingbird

Cuban trogon

That evening was our first visit to the nesting beach. We hadn’t been waiting long at the ramshackle shelter that houses the incredibly dedicated student volunteers before a green turtle was spotted nesting near the water. Unfortunately just as the turtle was getting ready to lay its eggs, a storm moved in with heavy winds that forced our group from the beach. By the time it passed, the turtle had returned to the ocean. Over the next three days and nights, our group explored the coral reefs of the park by snorkel and diving during the day, and returning to the nesting beach each night. Some in our group spotted a hawksbill while diving as well.

Green turtle nesting at Guanahacabibes. Photo: Jeff Frontz

The next two evenings we were treated to green turtles nesting and many in our group had opportunities to participate in the research by helping to measure the turtles, count the eggs, and walk the beach. The conditions that these turtles face on this beach are more challenging than most; between clamoring over exposed coral and dealing with roots and coral in the sand while digging nests, these turtles have to expend more energy than the average turtle nesting on a typical Caribbean beach.

We had originally hoped to have more than 3 turtles nest in four nights on the beach, but after two very high nesting seasons in previous years, the turtles were due for a down year this year. Our final night on the beach was idyllic; no turtles but a nice light breeze and full moon rising over the ocean as we waited.

Returning to Havana, our group dove headfirst into the extraordinary cultural treasures that we sampled the first night at the Art Factory. We were treated to a private concert by Mezcla, a well-known group that combines many styles of music including jazz, rumba, rock, and African rhythms. Many of our group took advantage of a last minute impromptu visit to the famous Cuban ballet for a wonderful performance of “Don Quixote” in the exquisite Gran Teatro and afterwards to see some local music at the famous Zorra y El Cuervo Jazz Club.

Pablo Menendez & Mezcla

Cuban Ballet performance of Don Quixote

The one time we came across turtles that was not a happy occasion was on a visit to a handicraft market. As we walked by one stall, the owner quietly mentioned she had turtleshell for sale (see photo at right). We stopped to document this illegal sale; items made from the shell of hawksbill sea turtles (incorrectly called “tortoiseshell”) are a major reason why this species is considered critically endangered. The good news is that our staff met afterwards with a local organization called “ProTortugas” who is launching a campaign to educate people about turtleshell and encourage people not to buy these items.

Fan made from hawksbill turtle shell for sale in Havana

Seeing these items for sale was sad but only serves to remind us why we do these trips and reinforces our need to take people to Cuba to work with sea turtles. By partnering with great organizations like CMRC and INSTEC, we can not only provide important financial support for conservation efforts but also help to educate travelers about wildlife-friendly shopping while there.

Ecotourism is proving to be a significant tool for supporting sea turtle conservation in Cuba, the tours that SEE Turtles and our sponsor Oceanic Society completed this year are providing $10,000 in funds to help protect the nesting turtles through our Billion Baby Turtles program. In 2017, we hope to provide even more support and to recruit other tour operators to spread the word about turtleshell products so we can reduce their demand.

Wild Blue Belize

As the EcoMar boat approached the dock on St. George’s Caye (an historic and beautiful island 30 min. from Belize City), a persistent buzzing sound hung in the air like a horde of angry bees. Fortunately for us, the sound came from a drone, used by researcher Eric Ramos to study the abundant manatees and dolphins found in these waters. Eric was looking for George, a resident manatee who spends most of his (we think it’s a “he”) time feeding on the seagrass around the island.

Footage by Eric Ramos of the City University of New York of George the manatee and historic St. George's Caye in Belize.

The drone is just one way that ocean wildlife is studied by EcoMar and Oceanic Society in the Belize Barrier Reef and surrounding waters. For a week, our group was there snorkel looking for sea turtles, observe and record manatees and dolphins by boat, and study conchs by hand. The ocean is the lifeblood of Belize’s economy, generating hundreds of millions of dollars a year in tourism and fishing income, and protecting its waters is a priority for many residents.

Our group of travelers participating in our Belize Ocean Wildlife Research Expedition mostly from the Portland Oregon area, started off the week with a snorkel, exploring a reef known as Gallow’s Point (named for a person, not the infamous device). Near the end of the swim, we were greeted by a loggerhead turtle who we watched swim from a distance.

The following day (Monday), our group split up in two to participate in manatee observation and a conch survey. The manatee group headed to the mouth of the Belize River, in Belize City, a popular hangout spot for the large marine mammals. To the delight of the group, one curious manatee surfaced near the boat as the group recorded the high pitch squeals of the more than dozen feeding in the area.

The area is a popular spot for local tour operators to bring people from cruise ships and then head upriver. Unfortunately many of the boat drivers don’t respect the “no wake zone”, driving their boats quickly through the area, which puts the manatees at risk. An estimated 30-40 manatees here die per year due to boat strikes according to Eric, something that EcoMar is hoping to address with an outreach campaign.

The conch survey was a favorite for many in the group. A weighted measuring tape was laid down in an area of seagrass and participants would search for conchs on either side within a meter of the line. Once found, the conchs were measured and recorded and returned to the ocean floor. This research is an important way to study where the conchs are most densely populated and what impact the conch fishery has on the population.

On Tuesday, the group’s stronger swimmers spent the day looking for sea turtles, snorkeling in a line keeping an eye out for the turtles. We spotted several green and hawksbill turtles though were unable to catch one to study. But the sightings will be documented as part of a database of turtle sightings around the country. The rest of the group participated in a dolphin survey, recording the behavior of bottlenose dolphins that inhabit the waters between the island and Belize City.

The highlight of the trip for many was the visit to Hol Chan, the country’s first marine protected area and a popular spot for snorkelers. After a 45 min ride, our boat pulled up to join a dozen or so other boats in the area near a well-preserved coral reef. We swam out to the edge of the reef, seeing a number of rays (stingrays and spotted eagle rays) and many reef fish and then came across what had to be the most patient green turtle I’ve ever witnessed, feeding on seagrass with a horde of people around it.

Next stop was an area where fishermen discard their conch shells and lobster heads. Two large loggerhead turtles found their way to this smorgasbord and were tearing into the lobsters with crunches that were clearly audible underwater. Unfortunately for the turtles, many fish and several rays also found the spot and proceeded to hound the turtles’ every attempt to get meat out of the shells. Their flippers acted both as hands to hold down the lobsters to crunch as well as to wave away the annoying freeloaders and the turtles resembled dogs with their beloved bones in their mouths as they tried to swim away from the fish.

Our last stop was an area full of nurse sharks, which aren’t aggressive to people (but do aggressively beg for food from the tourist boats that feed them). A horde of sharks approached our boat but only for a short time until they realized that we wouldn’t be feeding them (it’s not generally a good thing for sharks to be fed by humans). But we did get a chance to watch these graceful sharks underwater once they dispersed.

Our final day was nearly rained out, though with a group from Oregon, that wasn’t a deterrent. We did one more search for dolphins and then split in groups to do an additional conch survey and one final snorkel, where a couple of swimmers had the extraordinary luck to witness a spotted eagle ray launch itself into the air from underwater.

On Friday morning, our group reluctantly gathered before breakfast for a group photo, knowing it was time to leave this incredible ocean paradise. We gave our thanks to Linda & John who run EcoMar, as well as their great cooks and staff, and Eric with many promising to return again as soon as possible. We returned home knowing that our visit supported a bunch of important research and conservation efforts and dedicated people working to protect the extraordinary waters of Belize.

6 Tips for A Healthy Ocean

(Originally written for the Endangered Species Chocolate blog)

For decades, the ocean has been the ultimate dumping ground. Anything humans have ever wanted to throw away have been tossed ashore. The statistics are truly staggering, from a study saying there will be more trash than fish by 2050 to another saying that 5 large bags of plastic end up in the ocean for every 1 foot of coast, every year.

The problem is that “away” isn’t really away. That plastic comes back to us by contaminating our seafood, by killing animals that are important to ocean habitats and coastal economies like sea turtles and whales, by ruining beaches that used to be popular for tourism.

The good news is that this problem is fixable. This World Ocean’s Day, all of us can impact the ocean in a positive way. Here are a few tips to help make the ocean a bit more healthy.

1. Say Goodbye to Straws

It’s said that the human brain is the most complex thing in the universe. Do we really need a plastic tube to help get liquids from a drink to our mouths? Straws may seem innocent, but when you see video of a straw being extracted from a sea turtle’s nose, it’s enough to say “no straw please” the next time you order a drink.

2. Balloons Blow

Perhaps we could find a way to celebrate special occasions that don’t involve releasing a gaggle of balloons that often make their way to the ocean? In the water, with its string, a balloon (like plastic bags) can look a lot like a jellyfish to a sea turtle. If you are planning a celebration, consider other ways to have fun than releasing helium balloons and if you end up with a helium balloon, be very careful to keep it from flying away.

3. Reef-Friendly Suntanning

Did you know that our skin can be a source of pollution? Sunscreens that contain the chemical oxybenzone can damage coral reefs. Even a tiny bit can hurt; as little as one drop in the equivalent of six Olympic-sized pools can be damaging. PADI has put together a guide for sunscreens that are better for swimming in the ocean here.

4. Bear Your (Ocean) Sole

Flip flops are not generally made to last. They are one of the most common products found littering beaches around the world. In Kenya, Ocean Sole collects discarded flip flops from the beach and turns them into beautiful wildlife creations.

5. Shop Carefully on Vacation

In many tropical places, especially around Latin America, souvenir shops and artisans sell items made from the shell of critically endangered hawksbill sea turtles (sometimes mistakenly referred to as “tortoiseshell”). Keep an eye out for these items and avoid shops that sell them. Hawksbills are key to the health of coral reefs and their shells don’t grow back.

6. Law of Reduction

Countries, states, and cities around the world are taking action to reduce waste through bans or fees on plastic bags, Styrofoam, and other plastic. These bans can have a huge impact, a tax on bags reduced their use at least 75% in Ireland for example and a bag fee in Washington DC has reduced their use by 50% according to studies. Encourage your decision-makers to enact these policies is a simple act that can have a huge impact. And of course, remember to bring your reusable bag whenever you shop!

Facebook:

Twitter:

Take a Vacation, Save an Endangered Species

Guest Contributor Melissa Gaskill

If you want to help save an endangered animal, go on vacation. No, really. A recent scientific study concluded that ecotourism can make the difference between survival and extinction for some rare and endangered animals.

Researchers from Australia’s Griffith University quantified the effects of ecotourism for the first time using a scientific tool called population viability models. These models, widely used in wildlife management, estimate change over time in numbers of a particular species. The researchers ran the models using existing data for nine species, including orangutan, cheetah and African penguin.

Young traveler and a green sea turtle. Photo by Hal Brindley

According to study co-author Ralf Buckley, ecotourism boosted conservation of seven of the species. That’s because ecotourism tends to lead to measures helpful to wildlife, such as creation of private reserves, habitat restoration, anti-poaching measures, and removal of feral predators.

These results come as no surprise to those familiar with sea turtle conservation. Ecotourism has long been an invaluable part of worldwide efforts to save these endangered marine reptiles. Many conservation and monitoring projects rely on tourists to help fund their work, generating income by charging visitors to join beach walks looking for nesting sea turtles or hatchlings leaving the nest and to tour hatcheries and research facilities. Others depend on volunteers, who pay for room and board and spend their vacation helping with beach patrols, collection of eggs, maintenance of hatchery facilities, and hatchling releases. As an added benefit, the very presence of tourists deters poachers.

The study’s authors stress that not all ecotourism has a positive effect, and that is something the sea turtle community also knows all too well. Some “ecolodges” were built in prime nesting habitat, have bright lights that interfere with nesting, or allow activities on the beach that can harm sea turtles. Hotels on or near nesting beaches in some parts of the world charge guests a fee to ‘release’ a hatchling, even though handling is not good for the animals and the delay between hatching and reaching the ocean could prove fatal to them. Some places take crowds of people onto beaches to watch hatchlings emerge from the nest, without taking precautions against the hatchlings being trampled by careless tourists or disoriented by flashlights. Some have kept hatchlings in tubs of water for viewing by guests, sometimes for days. Even if these hatchlings are still alive when finally released into the ocean, they probably don’t survive.

Hotel built on a turtle nesting beach. Photo by Neil Osborne

Bottom line, ecotourism can make a positive difference if done right. It is up to you as a traveler to choose destinations and outfitters whose priority is protecting the animals and habitat rather than exploiting them. Biologist and author Wallace J. Nichols, ecotourism expert Brad Nahill (co-founders of SEE Turtles) and I wrote a book about sea turtle ecotourism destinations that operate in a responsible way. In general, keep these simple guidelines in mind. Avoid destinations that keep animals in captivity or allow tourists to touch, hold or feed the animals. Seek out local outfitters and guides so that your tourist dollars go directly to the community. Look for programs that educate tourists (and locals) about the wildlife, environment and local communities and that use local restaurants, accommodations and other services. When local residents can earn a living from ecotourism, they can conserve and protect their natural resources and hold on to their way of life.

Every year, more people seek meaningful encounters with wilderness and wildlife, especially endangered animals. We must take care that these encounters actually benefit those animals.

Melissa Gaskill is a freelance science and travel writer and co-author of A Worldwide Travel Guide to Sea Turtles, TAMU Press. Follow her on Twitter at @MelissaGaskill

Sweat The Small Stuff – Ridding the Beach of Microplastic

By now you have probably heard about the problem of plastic in the ocean. Whether it’s the discovery of the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”, the horrifying video of a researcher pulling a plastic straw out of a sea turtle’s nose, or the ambitious efforts of teen Boyan Slat to come up with a large scale solution, ocean plastic has been in the news a lot over the last few years. And with good reason, a recent study estimated that a large bag of plastic ends up in the ocean each year for every meter of coastline on the entire planet. Another study estimated that as many as one third of all sea turtles ingest plastic, confusing it for jellyfish, one of their favorite foods.

One solution to this problem is beach clean ups, which have been going on for decades. While these efforts have successfully kept millions of pounds of trash out of the water, beaches afterwards are not completely clean of plastic debris. The problem is that plastic breaks down into small pieces and become vectors for bacteria, making them especially harmful to beachgoers and wildlife, in addition to the toxic chemicals that plastic is made from. Marine microplastic also has the ability to absorb deadly toxic chemicals from ambient sea water. Lab research at Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology which Marc contributed to and co-authored found that all marine microplastics contain PCBs and a range of up to 200 other deadly toxic chemicals at over one million times background levels.

One of our partners, Oregon-based Sea Turtles Forever (whose green turtle nesting beach project in Costa Rica is supported by Billion Baby Turtles), is one of the few organizations tackling this problem. One of the hardest working turtle conservationists around, Marc Ward, developed highly efficient screens for filtering out the small plastic bits that get left behind. The Blue Wave teams (Sea Turtles Forever’s Microplastic Recovery Team) tackle stretches of Oregon’s coast, removing hundreds of pounds of debris with each clean up.

I had an opportunity to join Marc and his team recently for an event at Cannon Beach for Earth Week. It was an unseasonably hot weekend day at one of Oregon’s busiest beaches, but that didn’t stop a group of volunteer high school students and local residents from braving the strong sun to help filter the beach. It takes about 5 minutes to shovel the debris onto the screen, pick it up and filter, and then dump the debris, covering about 5 feet of beach. Blue Wave focuses on the “Back Beach zone”, where waves collect plastic and other debris. The screens, what they call the “microplastic filtration system”, can remove plastic pieces as small as 100 micrometers (the size of a grain of sand).

Blue Wave volunteers filter sand at Cannon Beach, Oregon

Marc’s work has not only helped Oregon’s beautiful coast; he has sent copies of his filters to organizations around the world. The screens have been sent to 4 countries and they have worked with researchers at the University of Tokyo and Northwestern to study this problem. The work of the Blue Wave team is both helping bring to light the problem of microplastics and offering a simple solution.

Learn more about the problem of plastic in the ocean:

2015 in Review

2015 was a banner year and we have all of our travelers, donors, sponsors, teachers, and students to thank for it! This year, we nearly doubled the number of baby turtles saved at 8 important turtle nesting beaches across Latin America, we trained 40 teachers, college students, and community leaders in sea turtle education, helped hundreds of students participate in conservation efforts, and much more.

Here are the highlights from 2015:

Billion Baby Turtles: 230,000+ Hatchlings Saved (500,000 total to date)

More than 20,000 critically endangered hawksbill hatchlings at important nesting beaches in Nicaragua and El Salvador through our partners ICAPO & Flora & Fauna Nicaragua.

150,000 endangered green turtle hatchlings at Colola, Mexico, the most important nesting beach for these turtles along the Pacific coast through the University of Guadalajara.

Nearly 40,000 endangered green turtle hatchlings at Guanahacabibes National Park in Cuba through Cuba Marine Research and Conservation

More than 10,000 endangered green and loggerhead hatchlings at Tulum National Park in Mexico.

Green turtle hatchling in Nicaragua (credit Hal Brindley)

Through our teacher workshops, we trained more than 40 Nicaraguan teachers, college students, and community leaders in sea turtle educational techniques and provided scholarships for them to bring their students to participate in local conservation programs. The workshops were done in partnership with Paso Pacifico and Flora & Fauna Nicaragua.

Our School Fundraiser Contest raised more than $5,000 to help save 5,000+ baby sea turtles. More than 350 students at 17 schools across the US participated.

We provided scholarships for more than 400 Latin American students to participate in local conservation projects.

We gave our popular sea turtle educational presentations to more than 700 students in the US.

Teachers visiting a sea turtle hatchery in Nicaragua (credit: Brad Nahill)

120 travelers visited sea turtle conservation projects in Costa Rica, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Mexico. These tours generated more than $100,000 for sea turtle conservation and local communities.

Of those travelers, 95 volunteered during their trips, completing more than 300 work shifts.

A young traveler watches a green turtle return to the water in Costa Rica (credit: Hal Brindley)

There's one final thing we want to do by the end of the year - save 1,000 more hatchlings! We're more than halfway there and need your help. Every dollar donated helps save at least one hatchling and each gift comes with great thank you gifts.

500,000 baby turtles!

When we launched Billion Baby Turtles 2 years ago, we had no idea how many hatchlings we could save and how fast we could save them, but we knew that with the help of travelers, green businesses, donors, and students, it could be a lot.

We are thrilled to announce that we have passed 500,000 hatchlings saved, a huge milestone! We focus our support on important turtle nesting beaches in Latin America, where small donations can go a long way towards protecting lots of endangered hatchlings and providing funds to hire local residents to patrol those beaches and help them get to the water.

With the help of partners and donors, we have accomplished a lot since our launch:

Saved 70,000 Eastern Pacific hawksbill hatchlings in Nicaragua and El Salvador, possibly the most endangered sea turtle population in the world with fewer than 1,000 adult females by supporting our partners ICAPO and Fauna & Flora Nicaragua;

Saved nearly 250,000 black turtle hatchlings in Mexico, a population once written off and now rebounding due to local efforts over the past decade due to the great work of the University of Guadalajara;

Saved 100,000 green turtle hatchlings at Guanahacabibes National Park, Cuba, the islands 2nd most important turtle nesting beach in partnership with Cuba Marine Research and Conservation and INSTEC.

Over the next few years, we will increase the number of hatchlings saved by offering new tours to destinations like Belize and El Salvador, starting new partnerships with socially-responsible companies, and through our annual School Fundraising Contest.

One great new way that people can get involved is to become a monthly donor, helping to save baby turtles all year long. Check out our thank you gifts at each level of donation here.

This success wouldn't be possible without help from hundreds of donors, travelers, and students as well as sponsors like Endangered Species Chocolate and Nature's Path / EnviroKidz.

Protecting Nicaragua’s Sea Turtles

Working with local organizations to protect sea turtles along Nicaragua's Pacific coast.

Saving Hawksbills and Olive Ridleys Through Tourism & Education

Our two boats rounded a bend in the mangroves and spotted two men in the water collecting fish and passing them to another person onshore. Though it was early, the sun was already strong as we patrolled the Padre Ramos Estuary, a key hawksbill site in the northwestern corner of the country. Our goal was to capture juvenile hawksbill turtles with nets to study and release and we were approaching one of the best sites to find them. Our partners Fauna & Flora Nicaragua (FFI), in partnership with ICAPO, manage this site, one of the most important hawksbill conservation projects in the world.

However, our first attempt came up empty and we soon learned why. The fishermen we saw nearby were using homemade bombs, which blow up an area of water. This is one of the most destructive forms of fishing, indiscriminately killing everything in its wake, including turtles and fish, and damaging the habitat. The blast may have scared turtles away, leaving us empty-handed. So we moved on to another nearby spot, where we spotted a turtle coming up for air. The fishermen hired by FFI, quickly set their net around the turtle, eventually pulling up the one we spotted as well as two others.

The research staff took the turtles onto a boat and collected important data including their health, length, weight, and tag numbers (tagging them if they weren’t already) and taking small tissue samples used to study their genetics. This was the first opportunity of our tour group, there in Padre Ramos for a week to volunteer with conservation efforts, to see the beautiful hawksbills that they traveled thousands of miles to see and help.

Our other reason for being in this remote corner of Nicaragua was to hold a workshop where we trained teachers about sea turtles and how to teach their students about these incredible creatures. We spent a full day with a group of local teachers, playing games and discussing why hawksbills are endangered and how they and their students can contribute. That evening, we headed over to the FFI hatchery, where local residents are paid to bring hawksbill eggs collected from nests around the estuary to protect until they hatch.

We were once again lucky to see more turtles, this time little hatchlings who had recently emerged from their nest. The teachers got a great opportunity to watch the research done on the hatchlings, which included measuring and weighing, before they were released to the water. These hatchlings are critical to restoring this population of sea turtles, believed to number less than a thousand adult females in the region from Mexico all the way to Ecuador. Every hatchling released gives hope that this population can recover from years of poaching.

Our Billion Baby Turtles project supports this work by giving funds for the egg collecting program which we raise from tours, school groups, green businesses, and individual donors. Over the past five years, we have donated more than $35,000 to support hawksbill conservation efforts, resulting in the protection of more than 70,000 hatchlings. We have also helped to bring volunteers whose energy and money help to fuel this important effort.

Later we hopped into our rental car for the long drive to the southern Pacific coast, home to the country’s biggest turtle nesting beach at La Flor Wildlife Refuge. La Flor is one of roughly a dozen beaches worldwide home to the “arribada”, a mass nesting event where tens of thousands of olive ridley turtles can nest at one time over a few days on a beach less than one mile long.

Here, we worked with conservation organization Paso Pacifico to hold another turtle education workshop for local teachers and that night headed to La Flor to walk the beach. Though we weren’t able to spot a turtle that night, our enthusiastic group was excited to begin working with their classes to teach them about the sea turtles that live in the area. In addition to the workshop, SEE Turtles also provides scholarships for the teachers to bring their students to participate in the conservation efforts and nearby turtle projects, so the impact will be spread to many local schools.

After the workshop, I wandered through the popular tourist town of San Juan del Sur, about 30 minutes from La Flor. Despite tours to La Flor being one of the town’s most popular attractions, it’s not hard to find jewelry made from endangered hawksbills at gift shops and tables set out by artisans around town. Artisans can sell this jewelry with little risk of being caught as enforcement of the illegal trade of turtle shells is non-existent.

Over the next week, I spent a lot of time at La Flor, working with Paso Pacifico to develop guidelines for improving turtle watching at the reserve. Turtle tours to La Flor is a big local attraction; nearly every hotel in the area offers tours and tours are offered around town by local operators. Each night I went to the reserve, between 50 and 100 people arrived even though there were few turtles. A lot of work will need to be done to ensure that the people coming to the beach to see the turtles aren’t impacting the turtles themselves.

Each night I awaited news of the arribada, which generally happens during certain stages of the moon but the turtles can be fickle, as I found. It seems everyone here has their own way to tell when the turtles are coming and nobody was seeing any signs of their arrival. On my last full night, one solitary olive ridley made its way up the beach, with a group of roughly 70 people watching while it laid its eggs.

I woke up my last day in Nicaragua assuming I would miss the arribada, on my “sea turtle bucket list” for more than a decade. I stopped by La Flor on my way to Managua to take a few pictures, only to find out that a couple hundred turtles nested late in the night – the start of the arribada. Five or so ridleys were still there on the beach nesting. Obviously I would need to alter my plans to return to Managua.

That day moved slowly as I waited for night to fall to witness the mass invasion of turtles. Heading over at sunset, the first few turtles of the night came out of the water with just a few people there to witness. As dark fell, more and more dark shapes emerged from the water as more and more cars arrived to the parking lot. The bright white lights of members of army soldiers shined across the beach, there to keep poachers from taking the eggs.

La Flor has tremendous potential to be a model spot for turtle watching. Done well, tourism to the reserve could help reduce poaching, support local communities, and inspire people to support sea turtle conservation efforts. As one of the few accessible arribada sites, it’s our responsibility to make sure this treasure protects its turtles and provides a great experience for people coming from around the world.

Exploring Cuba's Natural & Cultural Treasures

The large green turtle arrived to the beach as if on cue, just minutes after our group arrived to the main nesting beach in Guanahacabibes National Park, near Cuba’s westernmost point. We waiting anxiously for her to dig her body pit and start digging it’s nest, which is when we can approach without worry of scaring her off. One of our group volunteered to be the one to count the eggs as they fell, getting a front row seat to the action. The turtle spent more than an hour digging through the coral-filled sand to lay her eggs and then we watched as she made her way slowly back to the water.

This Cuba Sea Turtle Adventure was the result of more than 2 years of discussions, negotiations, planning, and marketing, the result of a fledgling partnership between SEE Turtles, the Cuba Marine Research and Conservation project, Altruvistas, and the Center for Marine Investigations. This partnership includes funding for beach patrols at this park through our Billion Baby Turtles program and developing a model for this project to become self-sustaining through educational and volunteer tours.

- - -

It didn’t take long to be introduced to Cuba’s reputation for long lines. A third of our group ended up in the slowest immigration line and were the last ones through to baggage claim. On the bright side, we expected that our bags would be waiting for us when we got through. We were wrong. It was another 3 hours before the last of our bags came out and darkness started to fall as we made our way to dinner. Taking advantage of the dying light, we had dinner at El Torre, a restaurant at the top of one of Havana’s tallest building, giving us a stunning view of the city and Caribbean.

Now free of the lines, we started the next day with a presentation from Dr. Patricia Gonzalez of the University of Havana on the state of Cuba’s coral reefs, which are some of the healthiest in the Caribbean. A walking tour of Old Havana allowed our group to compare the squares and buildings that have been beautifully restored with sections that are awaiting restoration. Few places in the world (especially in the America’s) have such an incredible mix of architecture from more than 5 centuries and every block has an important historical or cultural treasure.

The next morning, we boarded our bus to head to the Viñales Valley, a stunningly beautiful region that is in the heart of tobacco growing country, about 2 hours west of Havana. We stopped at an organic farm with a beautiful view of the valley for one of the largest family-style meals I’ve ever had, with plates coming non-stop for more than a half-hour while an acoustic band sang in the background. That evening, we headed out for a party with a “Committee for the Defense of the Revolution”, a neighborhood organization that acts as a form of local government. After a few words of introduction, the music started and soon our entire group was dancing with our new Cuban friends.

The next morning, we hopped again on our bus headed for Maria La Gorda, the resort near Guanahacabibes National Park. Our exploration of this incredible park started the next day with a bird watching tour; the participants braving hordes of mosquitoes to see some extraordinary birds including the world’s smallest, the bee hummingbird. That afternoon, our group snorkeled the reefs off the beach in front of the resort while a few, including myself, went diving, where we saw a beautiful young hawksbill sea turtle. We then rested up for the main attraction, the visit to the nesting beach where we saw the large green turtle.

The next day our group took a group snorkeling tour to explore the incredible reefs around the area. Guanahacabibes National Park includes some of Cuba’s healthiest reefs as well as nesting beaches and coastal forests. A smaller group went out again to look for nesting turtles and were rewarded with a smaller green turtle that we were able to observe for a short while before heading back to the resort.

On our last full day in Cuba, we drove back to Havana in time to check in at the Hotel Nacional, one of the country’s most famous and historic hotels. We were treated to a private rooftop concert at dusk by Pablo Menendez and Mezcla, one of Cuba’s most popular bands, which was followed by our best meal of the trip, a multi-course feast at La Casa, and then more music at the well-known jazz club Zorro y Cuervo (Fox and the Crow) in downtown Havana.

One final tour of the National Aquarium and souvenir shopping on the last morning wrapped up the trip before heading to the airport. To bookend our marathon wait for our bags the first day, it took our group about 3 hours to get through check-in and security, though thankfully the plane was late and nobody missed it (though there were a few missed connections in Miami). But getting acquainted with Cuba’s charmless airport did not distract from an incredible week of exploring the country’s natural and cultural treasures.

EnviroKidz & SEE Turtles Partner to Save Sea Turtles & Provide Unique Experiences for Families

SEE Turtles & EnviroKidz partner to help save sea turtles.

How can a vacation help save the world? EnviroKidz, the delicious kids brand of organic food company Nature’s Path, approached us in early 2014 to help launch their “Win an EnviroTrip” initiative, a way to get their customers out into the world to see wildlife and contribute to their protection. We jumped on that opportunity and just wrapped up three tours with Nature’s Path EnviroKidz to Costa Rica’s incredible Osa Peninsula and the impact was more than we could have imagined.

First Annual EnviroKidz EnviroTrip Impact:

8 sea turtles studied (5 greens & 3 hawksbills)

33 travelers brought to Costa Rica

Dozens of mangrove trees planted

More than 300 volunteer hours worked

4,000 baby turtles saved

Thousands of dollars generated for the local community

Nature’s Path EnviroKidz has supported sea turtle conservation through SEE Turtles since 2008 and has been one of our most important partners. Their financial support helped us launch an educational program which provides free lesson plans and other resources for teachers and brings kids to visit turtle conservation projects. They also helped to launch Billion Baby Turtles, which to date has saved more than 250,000 turtle hatchlings at 10 nesting beaches around Lain America.

On these trips families from the US and Canada, SEE Turtles and Nature’s Path staff, and researchers from Latin American Sea Turtles all got together to study endangered green and hawksbill sea turtles in the Golfo Dulce, a beautiful body of water between the Osa Peninsula and Costa Rica’s mainland. In addition, the participants supported a mangrove reforestation program and visited an organic farm to learn how chocolate is grown and produced.

Starting early each day, our groups boarded the small boats to head out onto the calm gulf for a 15 minute ride to the turtle foraging areas. The LAST staff set out nets to catch the turtles (the only way to study them here since they don’t nest in this area) and then whoever was game hopped in the water to help untangle them. Once set, we headed to the beach to wait for the turtles to arrive.

The LAST staff monitored the nets throughout the day and when a turtle was caught, it was brought to the beach and placed in the shade to study. With help from our participants, the research staff measured the turtles length, width, and weight, tagged them with little metal tags on their flippers (if they weren’t already tagged), measured their tails, and took tissue samples for genetic studies. Once done, the turtles were taken back to the water for release.

Besides working with the turtles themselves, LAST is also working to restore mangroves to the area. Mangroves are extremely important trees, providing nurseries for fish, protecting the coast from flooding, and helping to keep the water clean. They are also important for the sea turtles, providing food and shelter for the hawksbills. Our groups helped contribute to this work by planting mangrove saplings and helping to restore their nursery from flooding.

These trips were not all hard work though. One afternoon with each group, we visited a nearby organic farm to sample all kinds of delicious fruits and to see the whole process of making chocolate, from seed to fondue. The participants learned how organic farming can support wildlife and help keep chemicals out of the water, which helps sea turtles and other animals. Everyone left with a new appreciation for chocolate, the “fruit of the gods”, seeing how the seeds grew on the trees, through the drying and fermenting process, and sampling the deliciousness at the end with a fondue with tropical fruit.

Even though not every participant was able to see sea turtles, these trips had a tremendous impact on sea turtle conservation efforts and the local economy. A big thanks to Nature’s Path EnviroKidz for their support and for the hard work, great attitudes, and generosity of the wonderful participants from the US & Canada!

Exploring Drake Bay & Isla del Caño

Fully loaded with SCUBA gear, I leaned back off the side of the boat, falling headfirst into the cool water. After a second to get my bearings, I headed to the rope and made my way 50 feet down into the ocean with the dive instructor. Visibility was good with a fair current. Within minutes we saw our first shark, a white tip reef shark quietly resting near a large rock covered in coral. It didn’t take long to realize my top priority for the dive (other than finishing the certification of course), seeing a turtle (hawksbill I think) hanging out under a rock at the bottom.

Drake Bay

Isla del Caño is one of Costa Rica’s most popular dive sites, a small island in the southern Pacific region near the popular Corcovado National Park on the Osa Peninsula. Many consider it to be the next best thing to Cocos Island, a world-famous dive site way out in the Pacific ocean. The island and its surrounding waters are a wildlife reserve, protecting dozens of both terrestrial and marine species. Drake Bay is the beautiful stretch of coast where rainforest, dark sand, and deep blue water meet up and where divers and other travelers stay while visiting the area.

Getting to Drake Bay was more of an adventure than expected however. I was based in La Palma on this stay and had a few days of rest between taking volunteer groups to work with green and hawksbill turtles in the Golfo Dulce, a spectacular body of water between the Osa Peninsula and the southern Pacific mainland of Costa Rica. What should have been a quite hour-long bus ride turned stressful (and expensive) when the owner of the bus decided to leave a half-hour early, leaving me stranded and looking for a taxi.

Once on the way however, watching out the window as we passed through tiny little towns and over (sometimes through) small rivers, I relaxed and enjoyed the ride. Having brought many tour groups to explore this beautiful country over the years, I rarely get outside our standard locations to see new areas. The Osa is extremely well conserved, with more than 2/3rds under some form of protection, and the views along the way were incredible.

I stopped at El Progreso, a small town about 20 minutes before Agujitas, the beach town where most people go, instead staying at Drake Bay Backpackers, a small hostel run by Fundacion Corcovado, a local organization that works to protect the area’s wildlife, including sea turtles nesting on the nearby coast. While the hostel didn’t have the more upscale rooms and beachfront views available at Agujitas, it offered many benefits those other places could not, including immersion in small-town Costa Rica, an opportunity to give back to the community and reduce my environmental impact, and also to save quite a bit of money.

Drake Bay Backpackers (photo: Rob James / Fundacion Corcovado)

The hostel is a new and innovative way for Fundacion Corcovado to support the local community. Built by the organization, management of the hostel is being passed on to local residents and provides a local base for tourism for a town that most travelers only pass through on the way to the beach. They offer more than a dozen tours to explore the area’s rich wildlife, all run by local residents who are able to supplement their income. The hostel acts as a base of operations for the organization’s successful sea turtle conservation program, offering volunteers a place to stay while patrolling the beaches at night protecting olive ridley sea turtles.

The next day, I got a ride into town early in the morning to meet the dive instructors. The 45 minute ride to the island was calm and relaxing and we even had an opportunity to see a few dolphins before getting in the water. After a quick stop to register at the guard station on the island, we headed back to a shallow area to begin diving.

Welcome sign at Isla del Caño

Once in the water, it wasn’t long before I saw my first turtle hiding in a small space under a rock. It looked like a juvenile hawksbill but I wasn’t close enough to be sure.

Having worked with sea turtles on and off for more than 15 years, this view was different from my normal turtle experience, seeing them drag themselves up onto the beach to nest. On land, sea turtles are awkward and slow but their grace and beauty in the water is entrancing. We stopped to watch for a moment before it swam away with a few powerful strokes of its front flippers.

After the turtle, we made our way around an area called “Paraiso” (Paradise), an area of rock and coral formations with impressive numbers of stingrays, reef sharks, and large schools of fish. At one point, we approached an area of seagrass, long black blades moving with the current. Only it wasn’t grass I learned once the little blades retracted themselves into the sea floor, they were garden eels.

Back in El Progreso, I explored the town, walking down a quiet road lined with cow pastures and African palm oil plantations. Near a small creek, a turtle of another sort was making its way across the road. I stopped to explore this much smaller cousin of the animal I know so well, which I later learned was a white-lipped mud turtle. Back at the hostel, I received a tour of the hostel’s innovative water filtration system by Fran Delgado, the Administrative Director of Fundacion Corcovado. By filtering all its gray water (from the sinks and showers) and releasing it back to the ground, the hostel significantly lowers its environmental impact on the town. That evening, I had a great conversation with (soda owner and father) about the town and rural living over an excellent typical dinner.

White lipped mud turtle in El Progreso

Making my way back to La Palma after a few days of diving and exploring was as much of an adventure as getting there and made me realized that I didn’t miss much the first day by taking a taxi. A group of young travelers were well into their Imperial beers and about halfway through their packs of cigarettes by the time I got on board. Fortunately the volume and air quality of the inside of the bus improved dramatically when the group decided they preferred riding on top of the bus (up and down the same steep hills and through the same creeks). All part of the non-stop adventure that is traveling in Costa Rica…

Learn more about the Corcovado Foundation's turtle volunteer program here.

Plastic, Plastic, Everywhere

By Katie Ross, Outreach Manager

For the past couple decades, scientists have come to different results when estimating the amount of plastic in our world’s oceans because it is hard to gauge how much trash is really out there. But there is one thing they can agree on, there is too much and it is causing a negative impact on the health of all our oceans and the animals that depend on them. This problem will only get worse if we don’t take action and address this issue right now.

An article was recently published by John Schwartz in the New York Times about a study on plastic in the oceans that was published in the PLOS One journal. The team of scientists from the organization 5 Gyres, used computer models to estimate figures from their samples and came up with very surprising results. They predicted that there are “5.25 trillion pieces of plastic, large and small, weighing 269,000 tons could be found throughout the world’s oceans”. The leader of this study, Marcus Eriksen, says that a lot of the debris by weight is discarded fishing nets and gear. He suggests to solve this problem, an international program could be put in place to pay fishermen who bring in reclaimed nets.

It isn’t just industrial junk out there though, common household items can be found floating everywhere from toothbrushes to plastic bottles and bags. Even your discarded electronics like cell phones and computers are out there! Most of this trash makes its way to the ocean by floating down our rivers coming from landfills and other urban sources. The trash then gathers at gyres where ocean currents converge and sunlight and waves have a chance to break up the plastic into smaller pieces. I went to school in Hawaii for a year in 2008 and when I’d walk on some of the beaches I would see small pieces of very weathered plastic that was soft to the touch. I would pick up as many pieces as I could, but the stuff was everywhere and it seemed like more would wash up the next time I would visit that beach.

The small pieces of plastic may break up until they eventually become as tiny as sand particles. Eriksen and his team expected to find a lot of sand-sized plastic particles floating in their samples because their computer models predicted there would be. The tiny pieces weren’t as abundant as they estimated them to be in their samples so it left them to think that maybe they either sink to the bottom or wash up on beaches, or they might even be ingested by marine animals like fish and whales.

Whether it is small or large plastic pieces in our oceans, we know that hundreds of thousands of sea turtles, fish, whales, and other marine animals die each year from ingesting or getting entangled in debris. Plastic bags floating in the water look just like jelly fish so turtles easily mistake them for food. Once they are swallowed, they can cause blockages within their digestive system that can lead to death. Fishing nets and lines can entangle turtles and either injure or drown them by not allowing them to resurface to breathe. At this point, it's likely that every single sea turtle on earth has to deal with plastic, swimming through it, crawling through it on the beach as hatchlings, or confusing it for food.

It is easy to get overwhelmed thinking about all that trash in our oceans, but we can help by not adding to this global problem. The best way to reduce the amount of plastic entering our oceans is simply to buy fewer products made of plastic or that use plastic packaging. By using reusable water bottles, food containers, and shopping bags, we could greatly decrease the amount of plastic we use and depend on. Also, choosing whole foods and fruits rather than packaged and processed foods is a great way to use less plastic and to eat healthy. We can send a message to the companies that make all the products we use by choosing to only buy items that are created sustainably or have a smaller carbon footprint to produce. The health of our oceans affects us all, and everyone who is a consumer is contributing to this growing problem.

Learn more:

Sea Turtles, Dolphins, & Scarlet Macaws

By Brad Nahill, SEE Turtles Director

Our group of amateur marine biologists milled on a quiet beach on the Osa Peninsula in Costa Rica, anxious to head out into the calm Golfo Dulce (aka Sweet Gulf) to study sea turtles as part of a local research project. The calm was broken with a sudden screech from two passing scarlet macaws, their bright red color standing out against the light blue sky. The harsh call of this spectacular bird would become the soundtrack to our exploration of this peninsula, described once by National Geographic as “the most biologically intense place on earth.”